This article explains Blockchain: what it is and how it is used in finance, laying out the technology, real-world uses, and the trade-offs that matter to banks, regulators, and investors. I’ll cut through the jargon and show concrete examples of where blockchain is already moving money and where it still feels experimental. Read on for a clear tour of concepts, benefits, risks, and practical steps for institutions thinking about adoption.

- What is blockchain in plain terms?

- How does blockchain actually work?

- Types of blockchains: public, private, and consortium

- Key properties that matter to finance

- Primary use cases in finance

- Real-world examples and pilot projects

- Benefits and measurable efficiency gains

- Risks, limitations, and regulatory concerns

- Implementation considerations for financial institutions

- My experience observing adoption in the field

- The road ahead and what to watch

What is blockchain in plain terms?

At its core, a blockchain is a distributed ledger: a shared record of transactions that many parties can read and, depending on permissions, update. Unlike a single centralized database, the ledger is replicated across nodes that validate entries and keep a tamper-evident history through cryptographic linking.

The idea is simple but powerful — when each new block of transactions references the previous block with a cryptographic hash, altering historical records becomes extremely difficult without detection. That immutability, combined with network-wide validation, creates trust without relying solely on a single institution to guarantee it.

How does blockchain actually work?

Transactions are grouped into blocks and broadcast to a network of participants. Nodes collect these proposed transactions, validate them against protocol rules, and then add them to the chain when consensus is reached.

Consensus mechanisms vary. Proof-of-work requires computational effort to add blocks, while proof-of-stake and other algorithms use economic or voting-based systems to choose block producers. The mechanism affects speed, energy use, and who controls the network.

Cryptographic hashes knit blocks together: every block contains a hash of the previous one, a timestamp, and a record of transactions. Changing any data in a block recalculates its hash and breaks the chain unless an attacker also recomputes every subsequent block — a prohibitive task on well-distributed networks.

Types of blockchains: public, private, and consortium

Not all blockchains are open to anyone. Public blockchains like Bitcoin and Ethereum allow broad participation and transparency, while private or permissioned ledgers restrict who can join and what they can see. Consortium blockchains sit between those poles with a governed group of organizations operating the network.

Financial institutions often prefer permissioned designs because they retain privacy and governance controls while leveraging distributed ledger benefits. The choice of architecture influences regulatory compliance, performance, and interoperability with legacy systems.

| Characteristic | Public blockchain | Private/consortium |

|---|---|---|

| Access | Open to anyone | Restricted to approved participants |

| Transparency | High | Configurable |

| Typical use in finance | Token markets, payments, DeFi | Interbank settlement, trade finance, KYC |

Key properties that matter to finance

Several blockchain attributes are especially relevant to financial services: immutability, programmability, and decentralization. Immutability strengthens audit trails; programmability via smart contracts automates conditional payments; decentralization reduces single-point-of-failure risks.

However, trade-offs exist. Immutability complicates error correction, and smart contracts enforce code logic that can carry bugs. Evaluating these properties in the context of legal and business processes is essential before deployment.

Primary use cases in finance

Blockchain is not a one-size-fits-all solution, but it addresses specific pain points where multiple parties need a single source of truth. Below are the most mature and realistic applications in financial services.

- Cross-border payments and remittances that reduce intermediaries and settlement times.

- Post-trade settlement and reconciliation, cutting counterparty risk and manual matching.

- Trade finance and supply chain financing with shared document workflows and reduced fraud.

- Asset tokenization, turning securities, real estate, or art into transferable digital tokens.

- Smart contracts for automated escrow, syndicated loans, and derivatives lifecycle events.

Each case requires careful design around privacy, identity, and regulatory compliance, but pilots and production projects show measurable efficiency gains when those issues are addressed.

Real-world examples and pilot projects

Several deployments illustrate blockchain’s practical impact. JPM Coin, developed by JPMorgan, demonstrated bank-to-bank tokenized payments within a controlled network to accelerate liquidity movement between clients and the bank. That project signaled incumbent banks’ interest in tokenization rather than wholesale replacement of systems.

Ripple has focused on cross-border payments and developed partnerships with payment providers to route remittances faster and at lower cost than legacy rails in some corridors. While its business model and regulatory disputes attracted attention, the network model points to clear cost-saving opportunities.

Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) are another major trend. China’s digital yuan pilots are among the most advanced, and several central banks are researching tokenized currency designs to improve payments infrastructure and financial inclusion. These initiatives often use permissioned ledger components tailored to monetary and regulatory control.

Benefits and measurable efficiency gains

When implemented thoughtfully, blockchain can cut settlement times from days to minutes, reduce reconciliation costs, and lower counterparty credit exposure by enabling atomic transfers. It also creates richer auditability for compliance teams because transactions record provenance and timestamps across participants.

For example, trade finance pilots that replaced manual letter-of-credit exchanges with shared ledgers reported faster processing and fewer document discrepancies. The exact savings vary by use case, but improved straight-through processing and fewer intermediaries tend to yield consistent operational gains.

Risks, limitations, and regulatory concerns

Blockchain introduces new risks alongside benefits. Smart contract bugs can lock funds or execute unintended transfers, while privacy on public chains can expose sensitive transaction details. Permissioned systems mitigate some privacy concerns but reintroduce trust in gatekeepers.

Regulatory clarity is uneven across jurisdictions. Securities laws, KYC/AML obligations, and data protection rules apply to tokenized assets, and differing national approaches can complicate cross-border projects. Firms need legal counsel early in design to avoid surprises and ensure enforceability of on-chain actions.

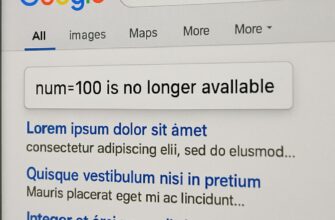

Scalability also matters: many public blockchains face throughput and latency limits that make high-volume financial workloads challenging without layer-2 solutions or alternative architectures. Choosing the right platform and designing for interoperability are critical technical decisions.

Implementation considerations for financial institutions

Adopting blockchain requires more than installing software; it demands governance frameworks, operational controls, and integration with core banking systems. Institutions must define who validates transactions, how disputes are adjudicated, and how keys and custody are handled.

Interoperability with legacy systems and other ledgers is often the hardest part of implementation. APIs, middleware, and standardized token formats help, but operational playbooks for failure modes and manual intervention are necessary until networks mature.

Security and custody models deserve special attention. Holding digital assets requires secure key management, trusted custodians, and insurance models for loss scenarios. Banks and custodians are actively developing custody services that meet institutional and regulatory expectations.

My experience observing adoption in the field

In reporting on fintech panels and participating in industry workshops, I’ve seen cautious optimism among bank technology teams. Early pilots often start with low-risk internal use cases like interoffice liquidity movement before moving to client-facing services. This phased approach helps teams learn about governance and operational risks without exposing large sums to immature networks.

Vendors and consortia play a significant role in these pilots, providing reference implementations and compliance support. When pilots succeed, the next hurdle is scaling governance across competing institutions — a social and legal challenge as much as a technical one.

The road ahead and what to watch

Expect continued hybridization: permissioned ledgers for bank and regulatory use cases, and public blockchains for liquid token markets and open finance. Layer-2 scaling solutions and privacy-preserving cryptography like zero-knowledge proofs will expand use cases that today seem infeasible at scale.

Regulatory developments will steer adoption. Clear rules on token ownership, custody, and cross-border data flows will unlock institutional investment. Meanwhile, technical standards for token metadata and settlement finality will ease interoperability between platforms and traditional systems.

Blockchain is not a magic wand, but it is a toolbox that solves specific problems around shared data, settlement risk, and automated contractual logic. For finance, the immediate wins are operational efficiency and new product models for tokenized assets, while the longer journey involves legal, governance, and technical integration work.

To explore more analyses, updates, and case studies on finance and emerging technologies, visit https://news-ads.com/ and read other materials from our website.